Top performers hold their ground in Australia

The fall in international student revenues from universities in Australia: The impact of the 2020 budget deficits on the higher-education sector of the United States and other countries

International students make up a significant part of the Australian higher-education sector. More than a quarter of all university revenue comes from tuition fees. Australian researchers would feel the effects of a fall in revenue from international students, with nearly 60% of Australia’s research expenditure coming from its universities as of 2020, compared with the United States at 45% and the UK at 42%.

“Since 2020, record numbers of universities have reported deficits,” says Andrew Norton, who studies higher-education policy at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra. The data shows that in Australia, over half of the 38 publicly funded universities were in the red. It was one a long time ago. The student numbers are also a concern. The first fall in total university enrolions in 60 years was caused by travel restrictions on international students. The following year, enrolments fell again, but this time, it was different: domestic student numbers were in freefall.

The cap will kick in at the beginning of the 20th century, pending parliamentary approval. Although the bill was originally supported by the opposition Coalition government, a surprise announcement in early November revealed the Coalition party intends to vote against the bill. Universities and other educational institutes have spent months planning for the caps, assuming they would be implemented.

Australian Universities Accord: How Research and Development is Diverse in the Early and Mid-career Era? A View from Kelly and Crossley

Kelly said the survey showed there were deep frustrations in the early andmid-career researcher community that could have lasting effects. As job prospects narrow, many are looking outside Australia for opportunities, and that could result in a brain drain which could impact the quality of Australian research in the long run.

Crossley is also hopeful that the sector can build strength and says the suggested changes to research funding in the Universities Accord is a great place to start. There are some suggestions that can help plot a path towards a more sustainable future for Australian research.

Ryan says there is an increasing focus on responsible research practices among Australian institutions, which should be reflected in research assessment practices. In order for institutions to improve diversity and inclusion they need to engage more often with local and minority communities to ensure that they have a say in research that affects them. The Universities Accord urges the sector to bolster First Nations’ involvement in the system, for example, by ensuring that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are in leadership positions to influence policy-writing, funding and programmes.

There are some amazing federal government policies and strategies that are elevating Indigenous commercial and conservation expertise in Australia’s economic future according to Emma Lee, a sociologist at Federation University in Victoria. Lee highlights the Sustainable Ocean Plan, a government initiative to manage and protect Australia’s marine environment, as an example of strong collaborative work. She notes how the Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water has centred Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the project and says their consultation work highlights the importance of informing food security and conservation policies with Indigenous ecological knowledge. She points to the need to collaborate with Aborigines to achieve the legislated goal of net zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050 and also says there is some good work being done in farming.

Research and development (R&D) intensity in Australia peaked in the 2000s during the mining boom. It has since declined, bucking the curve of other major Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development economies. Whereas the average R&D intensity of the OECD group grew from 2.3% of GDP in 2008 to 2.7% in 2021, Australia’s dropped from 2.25% in 2009 to 1.68% in 2022, its lowest level in 20 years.

Over the last decade, open access, or free to read, papers have increased. In 2015, 65% of ARC-funded publications were pay-to-read, according to Navigator, and 28% were free to read (the status of the remaining per cent is unknown). These numbers stayed relatively consistent until 2022, at the height of the pandemic, when free-to-read papers jumped to 47%. By 2023, 60% of papers were free to read and 29% were pay-to-read, and in 2024, which is an incomplete year, free-to-read publications account for 68% of ARC-funded output so far.

Computational models and algorithms and clinical studies and public health have the most publications for the period between 2015 and 2024, accounting for 103,840 and 101,586. Computational models and mathematics have 101,866 publications related to them. Within clinical studies and public health, 77,845 publications were related to the ‘clinical interventions and health services research’ subtopic, according to Navigator.

Australia recorded the worst drop in adjusted shares among the top 20 countries in the Nature Index between 2022 and 2023, indicating trouble for it’s research sector. Australia dropped from 10th place to 12th in just two years, overtaken by India and Italy.

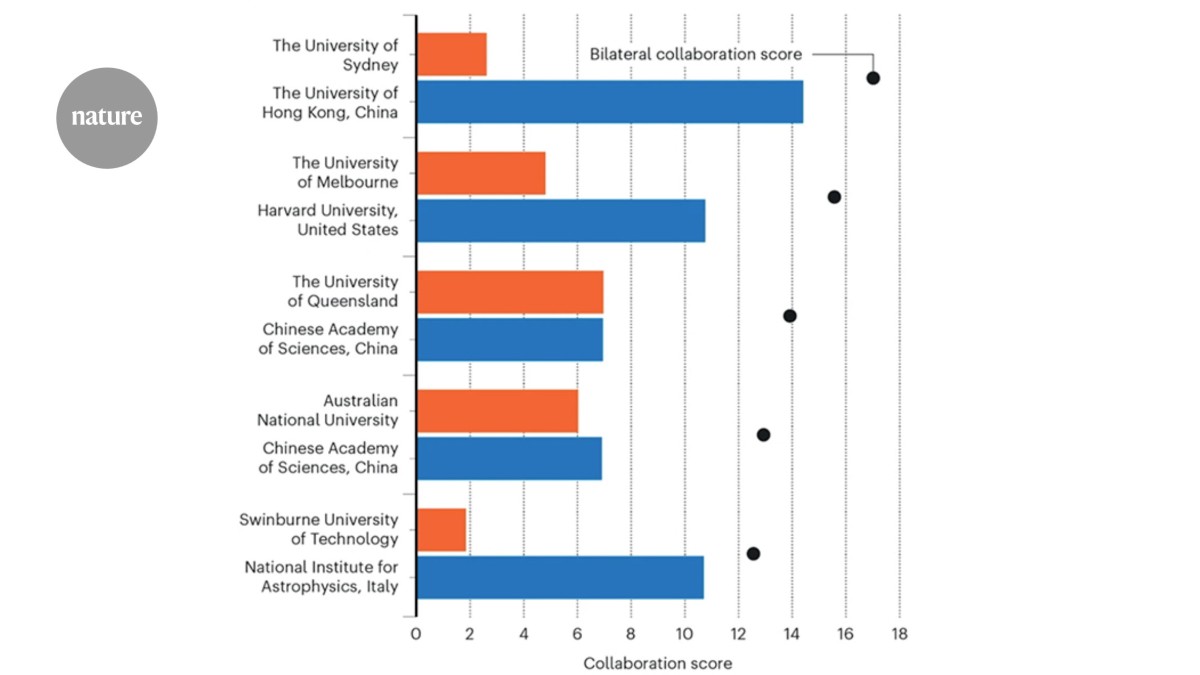

These charts highlight the strongest institutional players in a sector that needs to regain its footing in an increasingly competitive global research landscape.